The National Program of IT as the Alter-Ego of Procurement

"One of the worst and most expensive contracting fiascos in the history of the public sector."

Some real-life cases only require a little reflection to understand that the project was predefined for failure well before its launch.

Can we make appropriate conclusions to prevent that from happening again? The first step is to deepen our study of such cases beyond populistic cliches.

NHS IT System (2001-2011)

The national program for IT in the health service is the largest civilian computer project in the world. It was spawned in late 2001 and early 2002.

A far-reaching vision set out a program to transform people's healthcare experiences. Hospital admissions and appointments would be booked online—the choose-and-book system. Pharmacists would no longer struggle with GPs' indecipherable handwriting, and drug prescriptions would be handled electronically.

Politicians set the duration of the program at two years and nine months from April 2003 until December 2005. Given the extent of the proposals, that was a ludicrous timetable.

The study concluded that only some players could become prime contractors in a multi-billion-pound program. NHS soon announced that the procurement process for the program would be structured to attract global IT players. These players would only get paid once they delivered, and those not up to the mark would be replaced. In May 2003, potential bidders were given a 500-page document called a draft output-based specification and told to respond within five weeks.

When the then Health Secretary John Reid announced the contract winners in December 2003, the value of the contracts had already shot up to £6.2 billion from the original £2.3 billion. The time scale had tripled in length, and instead of the two years and nine months from April 2003 originally promised—the contracts were now to run for 10 years.

Four winning bidders were appointed: Accenture, Computer Sciences Corporation, CSC, Fujitsu, and BT. BT and Fujitsu chose a US software firm, IDX, to work with, while Accenture and CSC chose a British software company called iSoft. Lorenzo, iSoft's flagship software system, would be "available from early 2004."

Lorenzo caused a big headache for Accenture, as it had two contracts worth around £1 billion each. Accenture was trying to implement software that was unimplementable. CSC faced a similar problem in the northwest. As iSoft had not produced a working version of Lorenzo, neither Accenture nor CSC had any software to deploy.

There were significant concerns about the program's indifference to securing clinical buy-in from users—clinicians in hospitals.

Accenture and CSC struggled with the unusable Lorenzo. Eventually, a confidential report was produced in February 2006 stating that Lorenzo had "no mapping of features to release, nor detailed plans. In other words, there is no well-defined scope and, therefore, no believable release plan."

Accenture had two of the £1 billion-a-piece prime contracts, so it appeared to be facing a £1 billion penalty payment to the government if it abandoned the program. Strangely, Accenture engaged in swift negotiations with the health service, and in September 2006, after making a penalty payment of just £63 million, it duly exited the program. CSC quickly took on both Accenture contracts, tripling its involvement in the program. However, there were continuing problems at iSoft, supposedly writing the Lorenzo software.

Meanwhile, the other two providers, BT and Fujitsu, had their own problems. They were trying to implement American software IDX, which is not easy in a British hospital because American hospitals rely on billing for each activity and do not expect to have to handle waiting lists. In June 2005, Fujitsu dropped IDX and replaced it with another American firm, Cerner, which has a software package for large acute hospitals called Millennium. Some 18 months after winning its contract, BT struggled with IDX.

A group of health IT experts provided evidence that the program was likely to deliver neither the most important areas of clinical functionality nor the benefits required to justify the business case. The group stated: "The conclusion is that the NHS would most likely have been better off without the National Program in terms of what is likely to be delivered and when."

The program's central aim will only be achieved with the contract, which was massively overpaid. For example, acute trusts cost £23 million when they should have cost about £8 million.

The second issue concerns de-scoping. The program has dealt with its problems by drastically reducing the scope of what is being delivered but without corresponding cost reductions.

The third concern was with hiding increased costs. The late deliveries have meant no running costs for systems that have not been delivered, and the surplus cash is being used to conceal the increasing cost per deployment.

Fourthly, there were severe doubts about the platform's commercial judgment and skill. Very little of the expected initial system has been delivered, but the NHS needs more commercial cover. Fujitsu's termination from the program was farcical and generated massive potential costs and liabilities.

The fifth conclusion was the danger of future high costs. When the contracts are finished, inadequate provisions are made to manage the systems in the future.

The National Program for IT finally ended in 2011, although the enormously expensive and controversial project had been due for years to come.

Politicians set the duration of the program at two years and nine months from April 2003 until December 2005. Given the extent of the proposals, that was a ludicrous timetable.

The study concluded that only some players could become prime contractors in a multi-billion-pound program. NHS soon announced that the procurement process for the program would be structured to attract global IT players. These players would only get paid once they delivered, and those not up to the mark would be replaced. In May 2003, potential bidders were given a 500-page document called a draft output-based specification and told to respond within five weeks.

When the then Health Secretary John Reid announced the contract winners in December 2003, the value of the contracts had already shot up to £6.2 billion from the original £2.3 billion. The time scale had tripled in length, and instead of the two years and nine months from April 2003 originally promised—the contracts were now to run for 10 years.

Four winning bidders were appointed: Accenture, Computer Sciences Corporation, CSC, Fujitsu, and BT. BT and Fujitsu chose a US software firm, IDX, to work with, while Accenture and CSC chose a British software company called iSoft. Lorenzo, iSoft's flagship software system, would be "available from early 2004."

Lorenzo caused a big headache for Accenture, as it had two contracts worth around £1 billion each. Accenture was trying to implement software that was unimplementable. CSC faced a similar problem in the northwest. As iSoft had not produced a working version of Lorenzo, neither Accenture nor CSC had any software to deploy.

There were significant concerns about the program's indifference to securing clinical buy-in from users—clinicians in hospitals.

Accenture and CSC struggled with the unusable Lorenzo. Eventually, a confidential report was produced in February 2006 stating that Lorenzo had "no mapping of features to release, nor detailed plans. In other words, there is no well-defined scope and, therefore, no believable release plan."

Accenture had two of the £1 billion-a-piece prime contracts, so it appeared to be facing a £1 billion penalty payment to the government if it abandoned the program. Strangely, Accenture engaged in swift negotiations with the health service, and in September 2006, after making a penalty payment of just £63 million, it duly exited the program. CSC quickly took on both Accenture contracts, tripling its involvement in the program. However, there were continuing problems at iSoft, supposedly writing the Lorenzo software.

Meanwhile, the other two providers, BT and Fujitsu, had their own problems. They were trying to implement American software IDX, which is not easy in a British hospital because American hospitals rely on billing for each activity and do not expect to have to handle waiting lists. In June 2005, Fujitsu dropped IDX and replaced it with another American firm, Cerner, which has a software package for large acute hospitals called Millennium. Some 18 months after winning its contract, BT struggled with IDX.

A group of health IT experts provided evidence that the program was likely to deliver neither the most important areas of clinical functionality nor the benefits required to justify the business case. The group stated: "The conclusion is that the NHS would most likely have been better off without the National Program in terms of what is likely to be delivered and when."

The program's central aim will only be achieved with the contract, which was massively overpaid. For example, acute trusts cost £23 million when they should have cost about £8 million.

The second issue concerns de-scoping. The program has dealt with its problems by drastically reducing the scope of what is being delivered but without corresponding cost reductions.

The third concern was with hiding increased costs. The late deliveries have meant no running costs for systems that have not been delivered, and the surplus cash is being used to conceal the increasing cost per deployment.

Fourthly, there were severe doubts about the platform's commercial judgment and skill. Very little of the expected initial system has been delivered, but the NHS needs more commercial cover. Fujitsu's termination from the program was farcical and generated massive potential costs and liabilities.

The fifth conclusion was the danger of future high costs. When the contracts are finished, inadequate provisions are made to manage the systems in the future.

The National Program for IT finally ended in 2011, although the enormously expensive and controversial project had been due for years to come.

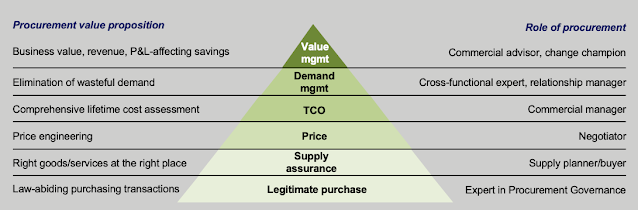

Procurement learnings

Unrealistic deadlines? Poor program management? Technological failures?

How did procurement award contracts to at least two suppliers who relied on iSoft without a working platform?

Contract management is another miserable story. Was there any SRM or stakeholder engagement? Risk management? Change management? Cost control?

I'm not trying to say that procurement was 100% at fault, but how can we claim our seat at the executive table when the most significant IT project in the history of public procurement demonstrates the total lack of any virtues we're so proud of?

Let's learn this story to face the alter-ego of procurement and try to spot any similar traits in our behaviors before it's too late, and we're dragged into projects that shouldn't have existed.

P.S. If you appreciate hundreds of hours invested in researching and writing this blog, you can buy me a coffee or subscribe for the membership by following this link. Thank you!

To keep receiving new insights and research, please subscribe here.

More information on this and other exciting topics can be found in "The Technology Procurement Handbook." It represents 23 years of experience, billions of dollars worth of successful sourcing projects, and 1000s hours spent on research, analysis, and content creation for the most demanding professional readers.

Comments

Post a Comment